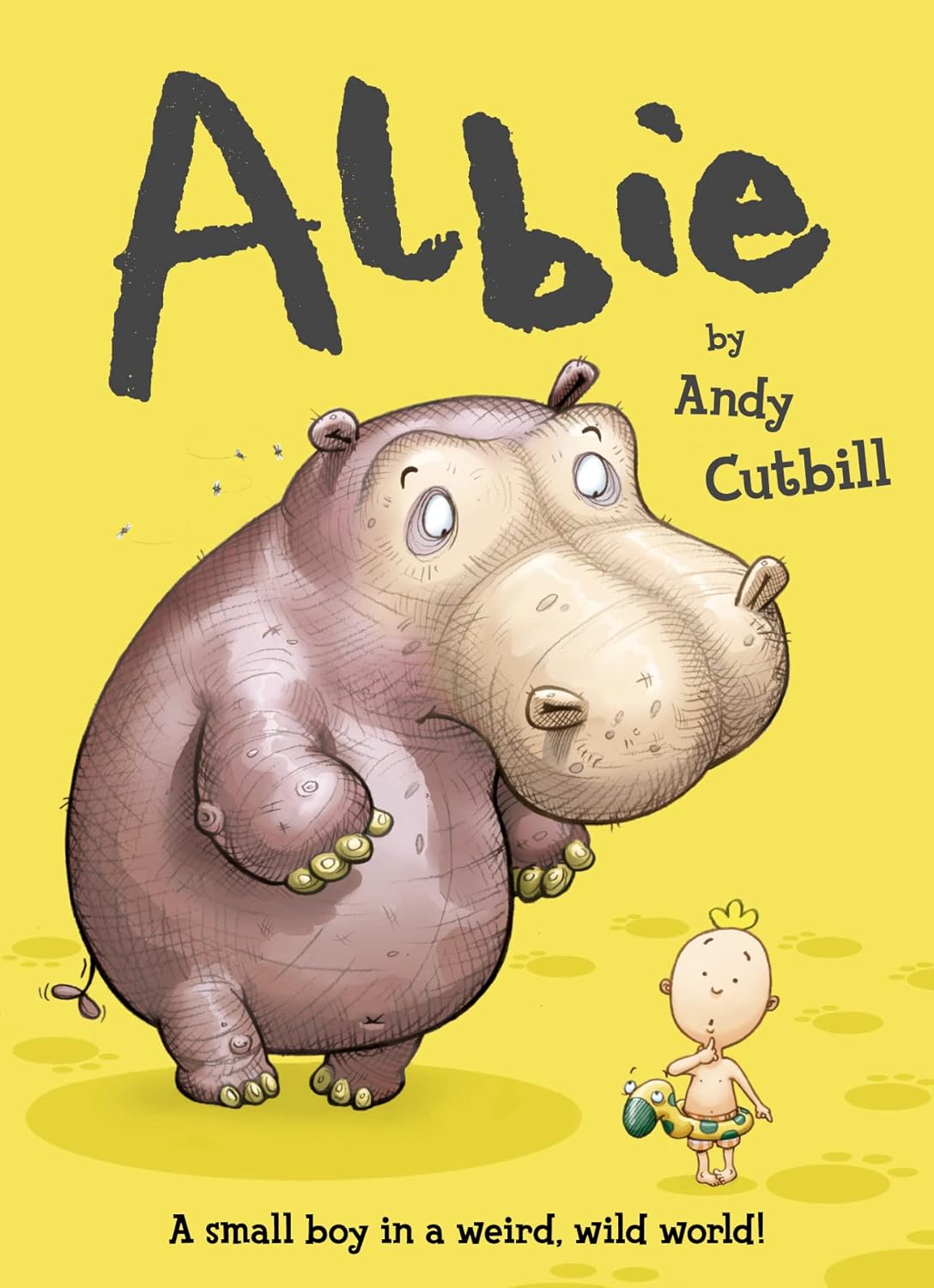

Albie

- Brand: Unbranded

Description

Albie awakes one morning to find himself the prime suspect in a serious crime. Mr. Kidhater-Cox's car has been stolen, and he demands justice. There was a writer called Geoffrey Trease who wrote stories about young boys who were involved in very historical episodes — Bows Against the Barons — fighting with Robin Hood. So you could identify with the poor, with the rebels, with the people fighting for a better life, and getting their sense of achievement and worth not through making money or scoring in football games, but through being associated with people fighting injustice. So all of these. But reading and reading. Jules Verne, and going to the moon, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, that sort of fantasy, the precursors of modern science fiction. By the way, I don’t enjoy contemporary science fiction, but as a kid I liked reading those books. Speaking of children, we’d like to ask you about your own childhood. To start at the beginning, where were you born? By the way, archaeologists really have discovered a flute made from bone and one clever person has even made a reconstruction that you can really play a tune on! If you’d like to find out more, you can watch his video here: Gosh, what I would love to see is disarmament, ending of nuclear weapons. I would love to see race becoming less and less and less significant. By “race” I mean all the stereotyping about people and individuals. I would love to see diversity being celebrated. It’s great that we’re different. It’s not something threatening, not forcing people into mainstream ways of doing things. I would love to see more joy and fun and laughter and dance and expressiveness. People are very timid. They’re very scared of being badly thought of or doing the wrong thing. You shouldn’t be afraid of doing the wrong thing, otherwise you’ll never get to the right thing. You take chances, and sometimes you want to cry because you’ve done something and it wasn’t correct. But you learn from that, you move on. I’d love to see people generally more adventurous. I’d love to see less risk and danger in the world, whether it’s danger from automobiles or from famine or floods or threats, danger from your partner. So many people are terrified of their partners. It just hurts me so much that you can’t love somebody and be close to somebody and express yourself physically to somebody, and (you) feel terrified. And yet it’s so common in all countries, amongst rich and poor. It’s just not a class thing or a color thing. Oh, there are lots of things I’d love to see.

And I started having some out-of-body experiences then. Very strange. I’m lying on my little cot, and I would feel Albie is lifting out, looking down on me. And I’m not a person given to a spiritual view of the world in that sense. I’m a great believer in the human personality and spirituality in that sense, but not an out-of-body experience. But I had them. They were quite, quite strong. I’m a little bit worried, but I carry on, I do my exercises, I run around the yard, I do my press-ups.

Follow us

I had met Stephanie Kemp who’d been, as it turned out, in the same prison cells I’d been in, and I was asked by an attorney to defend her. She was being charged with sabotage. And I said, “Please, I can’t. I identify so much.”“Just go and speak to her, give her some courage. When it comes to the trial we’ll get someone else.” Well they did get someone else to be the senior lawyer. Meanwhile I’ve fallen in love with her. We didn’t mention anything. We didn’t touch. We just spoke about the case and a bit about her past and sense of betrayal. But we were in love across the table, and she was sentenced to some years imprisonment, released. She came out to warn me that they’re coming for me again, that was my second detention. I still remember her saying, “And I was in that prison cell, and I got so angry with you because they all told me, ‘Why can’t you behave like advocate Sachs?’ And that pompous stuff you wrote up above the cell door, ‘I, Albert Louis Sachs, am detained here without trial under the 90-Day Law for standing for justice for all.’ Couldn’t you say it in less legal language?” And of course, even when I was writing that, I was careful not to say anything that could be used in evidence against me. I also wrote “Jail is for the birds” on top of the cell. I never set out to be a judge. I never imagined I would be a judge, but I became a judge almost by an accident of history. I’ve loved it. I love meeting judges in other countries. I had a glorious lunch at the U.S. Supreme Court. I met judges from the top court of the United Kingdom. I met judges in Kampala from all over East Africa and in different parts of Africa. We used to say, “Workers of the world unite.” Now I say, “Judges of the world unite.”

Albie Sachs: It was the last throw of the securocrats in South Africa, saying, “You’re facing the total onslaught. We have to be ruthless in our response.” They assassinated an ANC person in Paris, her name was Dulcie September. A bomb exploded the Anti-Apartheid Office — the ANC office — in London, and clearly I wasn’t safe in Mozambique. But you didn’t want to give way. You didn’t want to flee because of the danger. So many people inside and outside the country were accepting risks. What brought about that release, when you were released the second time? And then what drove you into exile?Albie lands in hot water when a herd of Welsh water buffalo try to spice up their singing act with a spot of diving. Months passed, and I’m at a party at the end of the year, and the band is playing. I’m very tired. We work very hard as judges. I hear a voice says, “Albie!” I looked around. “Albie!” My God, it’s Henri! And we get into a corner and I say, “What happened? What happened?” And he said, “I went to the Truth Commission, and I spoke to Bobby and Sue and Farouk.” He’s calling me Albie. He’s using their first name terms, people who were put into exile with me, who also could have been victims of the bomb. “I told them everything and you said that one day….” and I said, “Henri, only your face tells me that what you’re saying is the truth.” And I put out my hand and I shook his hand. He went away absolutely beaming, and I almost fainted. I heard afterwards that he suddenly broke away from that party. It was television people. He went home and he cried for two weeks. That moved me a lot. To me that was more important than sending him to jail. I wrote a book called The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter, saying that if we got democracy in South Africa, roses and lilies would grow out of my arm. Sending people to jail wouldn’t help me at all, but to get the country we’d been fighting for, that would be quite wonderful. That would be my soft vengeance. And now Henri and I — I don’t phone him up and say, “Let’s go to a movie.” But if I’m sitting in a bus and he sits down next to me, I say, “Oh Henri, how are you getting on?” We’re living in the same country because of the Truth Commission.

Did you come to know Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission? When did you first meet Archbishop Tutu? Albie Sachs: In my first year I was what was called a “good student.” I was on a scholarship. I got distinctions for Latin and Classical Culture and English. And it was unheard of for a law student to get the prize, the medal for English, but I got it then. And I did quite well in the early legal subjects. In my second year I got reasonable passes, and the lecturers, especially in English, wanted to know “What happened to you?” And what happened to me was politics, the world, the world outside. I did enough to get through at university. I got through my five years to get a law degree without ever failing, without ever repeating, but I didn’t get distinctions from then onwards. And 40 years later, Mandela appoints you to the highest court in the land. Amazing. In October 2009, you’ll be stepping down from the Constitutional Court. What are your plans? So I was younger than all the others, and they were sexually much more boastful than I could be and I was always worried about that. I remember going to a dance at University of Cape Town, and I had the advantage of being tall. That shouldn’t make any damn difference, but it counts. And I could talk, you know, quite confidently. I was quite good at talking. I read lots of books, I had been in our debating society. I loved quizzes. But I was terrified the girls would ask my age. ‘Cause what do you do? You meet somebody, and the first thing you want to know, “How old?” And I thought, “Gee, you know, she is 17 and I’m only 15. Just turned 16. She’s never gonna dance with me.” And I couldn’t dance then either. So I would see the question coming, and like five, six, seven steps away, like a chess player, I would turn the subject until I turned 21, and then suddenly I didn’t care anymore. So it was that mixed feeling of being very proud. “Gee, I’m brainy. I’m so young and I’m getting all these good scores, but I don’t want her to know.” It’s strange, but these things cost one a lot. You spend a lot of energy on that.It wasn’t an accident I read that, because there were many refugees from Germany whom my mother was very friendly with. And we even got her into trouble, because my brother and I went around very primly, aged about four and three, or five and four, telling the other kids, “You mustn’t say all the Germans are bad. You mustn’t say the Germans are bad. It’s the Nazis who are bad.” Again, you know, quite tough for a little four-year-old and yet, that was also combating stereotypes. Albie Sachs: Religion was, in the sense of being a very contested area. Ray and Solly fought their parents over what they regarded as the imposition of a religion on them. They were Jews. I’m a Jew. I was born into a Jewish family. It’s part of a culture, a history, a being, a personality if you’d like. But religion didn’t play a role in that, and it was very complicated for me. I was at a school where half the kids were Jews, half were Christians. I was a Jew by birth, association, culture, history, being, existence. But when it came to Jewish holidays, Christian holidays — some of them were public holidays like Christmas and so on — Jewish holidays, I didn’t feel it within me that I ought to take those holidays, because I didn’t belong to the cultural, religious side of things. Albie Sachs: It wasn’t conscious values, it was just being. Respect for somebody whom you admired. The total meaninglessness of a race as an indicator of what a person is like, what they mean, what they stand for, how you get on with them. I think that was probably the strongest thing. There was also a lot of humor, a lot of fun. This was now the beginning of World War II. Racism was being extolled by Hitler — Nazi Germany — as an ideal, and getting quite a reception in South Africa, because of our past. And I was growing up in a little home world that was completely different. The war ends, and courage is kind of in the air, not quite in that same intense way. And then the smart, attractive boy, and that’s seen as who will get the girls. Okay, it’s good if he’s good at sports and he’s robust and strong. It’s a continuation of the natural thing. But it was good to be clever, to be smart, to be brainy. That counted for quite a lot. And for years that continued, sometimes with the kind of war between the macho, hunky men — brave on the one hand — and the smart, clever guy who could be seen as a bit of a nerd on the other.

- Fruugo ID: 258392218-563234582

- EAN: 764486781913

-

Sold by: Fruugo